Who Knows?

Don’t drown the donkey.

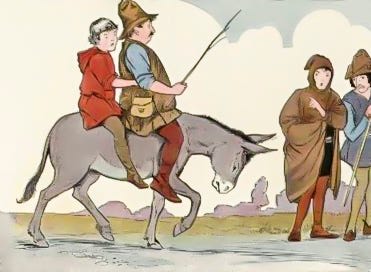

Roughly six hundred years before Christ was born in Bethlehem, a Greek fellow by the name of Aesop told a story about a farmer and his son. It seems these two were heading to market with a donkey for sale or trade, inhaling the fresh Mediterranean breeze and soaking up the warm morning sunshine, when someone traveling in the opposite direction made a comment on their mode of transportation: “Look at these fools! A strong, healthy donkey to ride, but they’re both walking. What a waste of energy.”

Dear me, thought the farmer, that is true, though I hadn’t given it a thought. “Here, son,” he said kindly, “why don’t you save your energy and ride on the donkey? We’ve still a ways to go.”

The son mounted the donkey and they jogged along at a slightly improved pace (or not – I wasn’t there but I do know a bit about donkeys). The sunshine wasn’t quite as pleasant – it never is when you’re thinking about how you look to others – but they had just begun to notice the scenery again when more travelers happened along. One of these voiced his own opinion on the three market-goers: “Ah me! The times we live in – look at that! A sturdy boy riding a donkey while his venerable father walks behind. No respect for his elders. Here, boy! You ought to be ashamed of yourself! Get down and let your father ride!”

Mortified, the lad swung down and his father mounted the donkey, definitely causing it to slow down. But they had not gone far when a group of women carrying water took notice of them. “For shame! Look at that selfish man riding comfortably along while the little one trudges behind in the heat and dust!”

This was terrible. The father turned to look at his son; he was rather sweaty and tired-looking. “Here, lad, get up behind me - he can carry both of us.” So the boy climbed up behind his father and the donkey moved on (more reluctantly than ever, I’m sure). But as they neared the town, they heard an angry voice from a knot of onlookers by the wayside: “How heartless these peasants are. Look at that poor beast – he must be nearly dead. How can they work him so cruelly?”

The farmer and his son looked at each other, thoroughly ashamed. “Let’s carry him, shall we?” the farmer proposed. So the two of them hoisted the donkey up and headed across the bridge into town. But halfway across they met a merchant who sneered, “Of what use is a beast of burden that must itself be borne? Surely you won’t get much for that carrion - you might have buried it at home and saved yourselves the trouble of coming to market in the first place!”

And here the story tragically ends, for even the most patient and compliant of people-pleasing farmers can be pushed too far. This one lost his temper, exclaimed “Drat the lot of them!” or its Greek equivalent, and flung the donkey off the bridge and into the river.

No doubt Aesop told this story in order to emphasize that everyone’s truth is valid and equally important; after all, each observer makes excellent points. Some travelers are maddeningly inefficient; some youths are self-centered and inconsiderate; some parents are self-centered and negligent; some livestock owners are self-centered and cruel; and some people are just foolish. It happens that the farmer and his son were merely foolish, but how could the bystanders have known that?

Or maybe that’s the point. How could they have known enough to form an opinion worth noticing?

Discussing prudence in The Four Cardinal Virtues, Josef Pieper says this:

There is a type of moral preaching closely akin to voluntarism, but held by many to be particularly “Christian,” which interprets man’s moral activity as the sum of isolated usages, practices of virtue and omissions. This misinterpretation has as its unfortunate result the separation of moral action from its roots in the cognition of reality and from the living existences of living human beings. The preachers of such “moralism” do not know or do not want to know—but more especially they keep others from knowing—that the good, which alone is in accord with the nature of man and of reality, shines forth only in prudence. Prudence alone, that is, accords with reality. Hence, we do not achieve the good by slavishly and literally following certain prescriptions which have been blindly and arbitrarily set forth…

The immediate criterion for concrete ethical action is solely the imperative of prudence in the person who has the decision to make. This standard cannot be abstractly construed or even calculated in advance; abstractly here means: outside the particular situation. The imperative of prudence is always and in essence a decision regarding an action to be performed in the “here and now.” By their very nature such decisions can be made only by the person confronted with decision. No one can be deputized to make them. No one else can make them in his stead. Similarly, no one can be deputized to take the responsibility which is the inseparable companion of decision. [Emphasis mine.] No one else can assume this burden.1

Aesop’s farmer, and these words of Pieper’s, both come frequently to my mind in the context of much current discourse on parenting and relationships.

has repeatedly noted the overly prescriptive tendencies of much conservative Protestant teaching on marriage and family matters. She’s largely right, I think, and yet even worse than the prescriptive focus of the teaching itself is the readiness of entire strangers to apply those prescriptions to random people with whom they’ve never meaningfully interacted and likely never will. But the reverse is also true; many people will react to a stranger’s assertion of some general principle as if it is a personal attack. What is needed all around is a little humility and an appreciation for the fact that applying moral principles to real life situations can only be done in real life.To take a recent example: should a young, single Christian woman, who hopes to get married, pursue a college education? Surely this is a question that cannot, by its nature, admit of a conclusive answer. A generic Young Christian Woman exists only in the abstract; a college education, on the other hand, must be pursued by this woman, or that woman, or the young lady next door. After all the valid points have been made about the enriching value of a good college education, or the economic value of a mediocre college education, or the corrupting influence of a bad college education, it is still a question that can only be answered in the context of a real life, by the one who will own the consequences of the decision - ideally with the wise counsel of those who know her situation and love her enough to have some stake in it themselves.

Should an unhappy spouse stay in a marriage? Why, yes, in principle. “What God has joined together, let not man put asunder.” Now, I’ve watched two marriages with small children collapse in the past two years. In one case, the wife fled with the child because her life was threatened by her husband. In the second, the wife filed for divorce shortly after the birth of their first child because her husband was unwilling to sell the farm he’d inherited from his parents in order to help fund her hobby. Neither of these details would have been accessible to the casual observer, let alone a keyboard warrior pontificating - even truthfully - on the evils of divorce.

I am in no way arguing for moral relativism. Right and wrong do not change with the times or the circumstances. But those circumstances do matter, and the application of timeless, unchanging moral truths to specific circumstances has to be done by the responsible parties, not by strangers, influential voices, your favorite online theologian, or “thought leaders” (whatever they are). Pieper again:

There is no way of grasping the concreteness of a man’s ethical decisions from outside. But no, there is a certain way, a single way: that is through the love of friendship. A friend, and a prudent friend, can help to shape a friend’s decision. He does so by virtue of that love which makes the friend’s problem his own, the friend’s ego his own (so that after all it is not entirely “from outside”). For by virtue of that oneness which love can establish he is able to visualize the concrete situation calling for decision, visualize it from, as it were, the actual center of responsibility. Therefore it is possible for a friend—only for a friend and only for a prudent friend—to help with counsel and direction to shape a friend’s decision or, somewhat in the manner of a judge, help to reshape it.

My point here is to distinguish between neighbors – those with whom we share a real life in community and, consequently, whose situations we have some knowledge of and in whose well-being we have a real interest – and members of an audience, whether online or at a conference or on a street corner, whose real life circumstances are beyond our knowledge. Counsel or specific application that might even be our duty in the first instance will often be irrelevant at best, harmful at worst, in the second.

Abortion is murder. Glyphosate herbicides are an immoral application of technology. Husbands, love your wives. Families should care for their own elderly members. These are general moral propositions that are worth defending. They are not the same as That woman clearly doesn’t care about her unborn child. You shouldn’t be feeding that cereal to your kids. Your wife shouldn’t have to drive a car that old. They ought to keep Grandma at home with them.

Online conversation is peppered with people who do not seem to know the difference.

The gender wars are fueled by many things, but a failure to grasp this essential truth is one of those things: responsibility and authority are inseparable. If you are responsible for the outcome, you have the moral authority to make the decision; if you have the authority to make the decision, then it is your responsibility to make it and own the consequences. If we would take the energy we sometimes expend applying truth to other people’s situations, and instead direct it toward encouraging each other to own our responsibility and apply those truths ourselves, it seems to me that many conversations and debates would become more edifying.

Josef Pieper, The Four Cardinal Virtues (Harcourt, Brace, & World, 1965), 24.